Don’t you feel like some teachers in your life are special and deserve to be inducted into your personal “Teacher Hall of Fame”? One of them was my 2018-19 English teacher of AP Language and Composition. She was widely regarded as one of the toughest teachers at the school, which gave me even more incentive to learn as much as possible from her, and drill and run my way through the class to success. Now it’s 4 years later, and I still remember her—and the class—well. As advertisers say about brands, the most successful ones have a salient and memorable phrase. Hers is “Be Concise and Be Precise” regarding writing across the board.

I’m a writer. I love to grind and distill my thoughts onto pen and paper (or adapt them to computer): grind, by churning out my thoughts en masse and laying them bare on the paper; distill, by refining my thoughts, structuring them, and creating a flow. Writing falls under the confines of strategism1, which for me is the Triplex Mindset. With writing, I have two paradigms—grinding and distillation. In grinding, one simply writes, as surely as some coders just code as soon as they open their computer—the thoughts flow naturally and spontaneously. In distillation, one first conceives of a structure, compartmentalizes the essay, and then writes paragraphs to follow that structure2.

That’s where we say goodbye to grinding, as it has little to do with concision and precision. And it’s where we discuss distillation, as both concepts are fundamental to successful writing. The two concepts aim for the same goal: clarity. In practice, they cut through a phenomenon I struggled with, and most writers have to trim down on: vagueness. It’s become all too easy to insert useless phrases that, while appealing on the surface, fails to convey deeper significance. When one analyzes Shakespeare and calls his writing a “brilliant, great work of time”, that’s vague and meaningless. When terms like “to color her language, the author uses syntax” are deployed, they are not just superficial, but confusing.

Precision comes in being specific with vocabulary, and avoiding the adjective soup that accompanies weak verbs, such as “very much angered” instead of “enraged”. The danger of the former phrasing is that it cheapens the worth of supposedly extreme adjectives; the adverbs “totally” and “extremely” have lost their weight because they are used far too often in modern language. In another direction, imprecision is terrible when inflicted upon theses of papers. Weak, vague analysis like “to color her language, the author uses syntax” is particularly damaging because such imprecision appears in the most critical part of an essay—the thesis. It’s the keystone and most difficult part of a paper3, so it ought to be especially strong to hold the entire paper together. One of my issues as a writer was avoiding direct and laser-sharp one-word verbs and settling for a cloud of adjectives; I found this to be wrong due to the necessity of precision.

With precision comes concision. Once the vague adjective soup is killed, a paper will naturally become shorter. But shortness is not the most notable quality. Density of material is. In mathematics, we often refer to textbooks which contain a high amount of results, equations, and significant progress as “dense”, as they do so in frighteningly little space, making them formidable to read. Similarly, great writing will force frequent contemplation, and express their range of attitudes and ideas in comparatively little space.

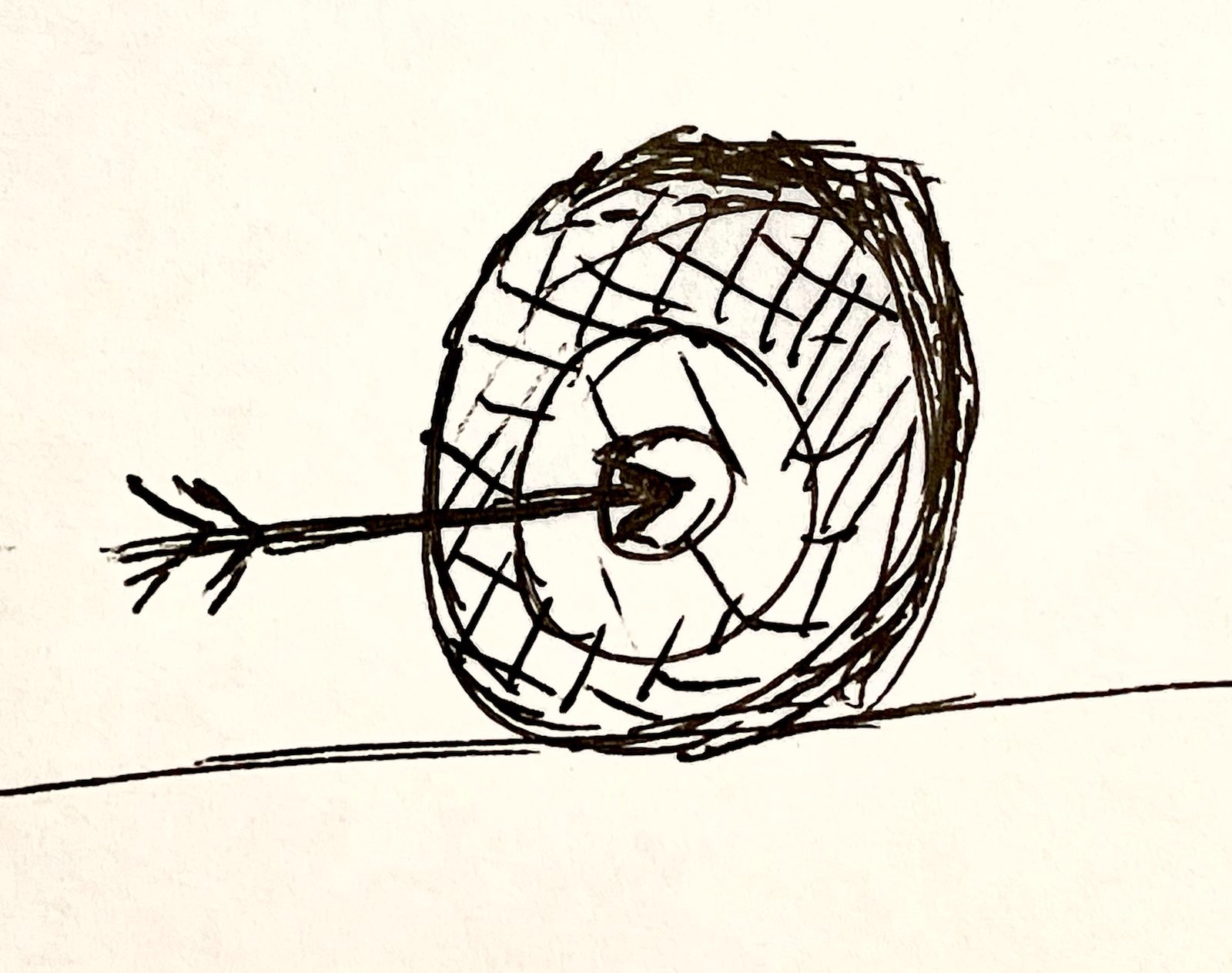

If we establish the importance of precision and concision, what’s the relationship between the two? I posit that concision comes as a result of precision: I would imagine hitting a bulls-eye as opposed to a 7 or 8 before I imagine hitting a bulls-eye in the least possible number of shots. Precision on existing writing leads to concision; English students (including I) are often shocked when they slice down the fluff in their writing, and the paper is only half as long as it was before. Meanwhile, concision does not necessarily lead to precision, especially if words are trimmed the wrong way, or ideas cut out to avoid exceeding page limits; extending this line of thinking, usually, one should seek to increase density of current thought in an essay, not cut out arguments, to reduce length. That would lead to a discussion on idea flow, organization, and relevance, which is a topic for another time.

Footnotes

1 A term I invented to mean “the belief that the world, or a subset thereof, can be explored and explained by strategy and tactics. The most prominent example thereof is the Triplex Mindset”.

2 A difference between writing and coding is that in coding, distillation reigns supreme 95% of the time, as large projects require careful thought and design. In writing, however, it is more than acceptable (and my default mode) to just start writing, have some sort of organized structure in one’s mind, and then refine later.

3 though essays like this one get a break because it’s not analytical, and structure strength is not as important relative to e.g. a formal paper of literary analysis.