I'd like to think that music, particularly piano, was my bright spot in early high school. The allure of mathematics, having defined my first 10 years, had receded, and I'd suffered an early-life crisis. With piano I could capture strength as if ordained by God, maturity beyond teenage expectations, and beauty, internal, fundamental, yet frustratingly indescribable.

May 2016 saw me capture a perfect 100/100 on Trinity College London's1 Advanced Piano exam. It won me an Exhibition Award for the highest score in North America2. That summer I asked my piano teacher3 what lay beyond the horizon, and she collected her thoughts, as if scanning into the unknown, slightly fearful of what lay next.

It was ATCL—Associate of Trinity College London—a diploma which indicated mastery of piano to a first-year undergraduate level. That would mean I was hitting 4 years above my range. She was visibly deterred, warning me that no one she had taught had ever ventured there, and that two others had tried and died, but I knew it had to be done. It was for the love of piano, the salient in my life, a source of happiness, exploration, and creative imagination. It was a chance at conquest, of blazing a new standard, of proving that music is music, piano is piano, and that all the other factors we condition4 ourselves on—age, others' success or failure—were meaningless in the face of great performance.

'Pressure' was ignored. I don't internalize it, and it simply doesn't get to me—I suppose that's my nature. One could argue that I didn't have pressure because I had nothing to lose, or that I had much pressure because winning would yield so many dividends, but the truth is, I didn't even consider the question. When faced with an enterprise as sublime and transcendental as music, I let that beauty be my primary guidance, in spite of the allure of exam glory5.

The first step was repertoire selection. I wanted a diverse set of pieces that would convey the breadth of music, challenge me technically, and allow me to advance my understanding of music. Naturally, I relied on my favorite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, and his signature anger rang true through the appropriately-titled "Rage over the Lost Penny"6. To complement the ball of energy, I selected the beautiful, singing, sad song of the lark in Balakirev's "The Lark". Providing additional depth in beauty would be Schubert's "Sonata in A Major, D 664", while Bach's "Toccata in E Minor" offered a baroque undertone, and Debussy's "Toccata"7 issued a final flourish.

The most 'systematic' of the pieces was Bach's, with a somber introduction and strong bass intonation. Sections were clearly delineated, as was customary of the Baroque era, and phrases worked within the rules of standard tonal music. One could imagine swapping the 16th-notes with chords instead, and indeed that's how I conceptualized and memorized the piece. An Allegro section demanded energy and flair, while the resulting fugue required color, achieved through repeated switching in melody and countermelody and note embellishments. I imagined myself playing a harpsichord, and transposed that onto the piano8.

A beautiful sonata came next, skipping a century ahead, not too big a jump by classical music standards. It was by far the longest of the pieces, with 17 minutes on the beautiful Styrian (Austrian) landscape, as Schubert intended. The first Allegro moderato movement demonstrated a flyover view of the mountains and valleys, with sparkles of sun with the high treble staccato scales, responsive appreciations from the people below in the bass, and a theme, often stuck in my head in practice, iterated and modified throughout the movement. The Andante offered a prayer to God, a gentle narrative of sunshine and happiness, gloom and fog, and then a return to sun as confessions were made, and balance restored. Finally, an exciting Allegro awaited, its pace surely indicative of children playing, a staccato rhythm that offered beaming hope and triumph, the technically most challenging movement, given the wide range in the left hand, particularly in bouncy passages.

Beethoven's piece was my favorite, for it offered some rage, but not a seething, intense one; the character of a playful boy who lost a penny must be displayed throughout. The increasing intensity of the melody and devastating 'attack' scales later subside into philosophical pondering, as the boy reflects on where the penny was left, and when he finds an answer, a new G major theme picks up, using short sections of the original fervor. Anticipation builds as the boy grows convinced he has left it outside while playing, and at the end, he finds it, a fitting conclusion to a youthful narrative.

While the boy is treasuring his penny, above him sings a bird, pining, despondent. It weeps softly, but does not mourn; it flutters all around the land, from the treetops to the branches, as if searching for some intangible quality. Though "The Lark" and the "Rage" appear opposite in style (slurred, pedaled passages versus staccato dynamism) and demeanor (a gentle, dignified song versus a lighthearted, energetic punch), they both represent searches, and in phrasing, can be thought of as iterations of the initial theme, though they do it differently. In "The Lark", we open with an essentially one-handed theme, which grows in conviction until we hit what could be interpreted as dozens of birds chirping, but is to me the multitude of inner thoughts of that single, frenzied lark; after a long, drawn-out voyage in flight and in thought, the bird undergoes catharsis and returns, in the same peaceful state as it was before the piece started, in B-flat major.

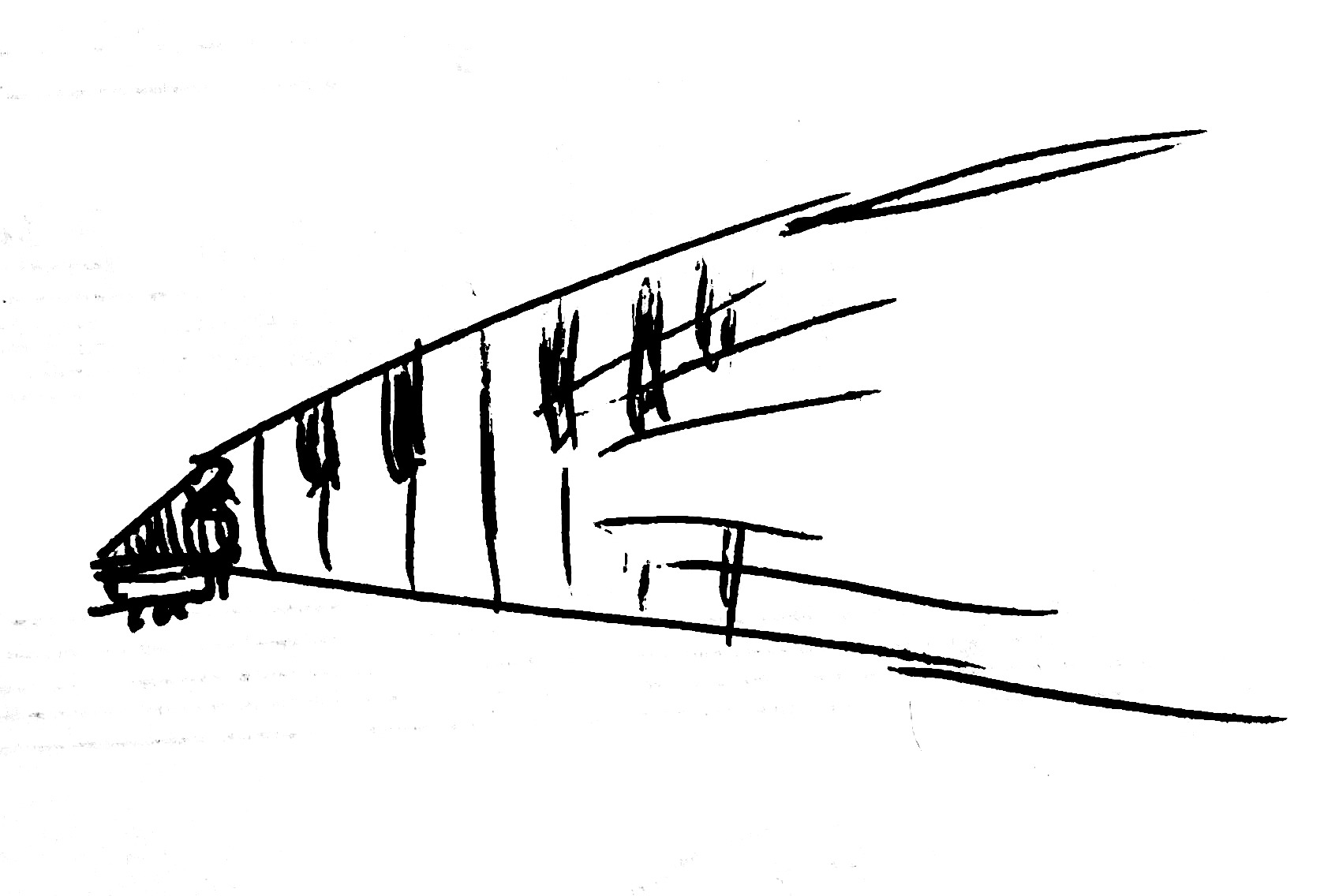

The four pieces, presented in the order of description, would suffice to create a well-rounded, robust program of musical exploration for ATCL, but I had to end with a spark. Debussy's scintillating Toccata captured the brilliance of puncturing through the high school music mentality and flying above. The entire piece can be rendered as 11 separate and short themes, sewn together with a thread of underlying vigor. There is no breathing room, no end to the continuity of 16th notes in arpeggios and accent strikes, and the beauty of the Toccata is that one does not easily associate it with a tangible vision (though an airplane the size of a bird swooping and dropping bombs on the ground appears half-applicable), but instead an abstract energetic outburst. One is left with a feeling of glory and triumph, spirited and quick, as if from above.

(And now you know where my title comes from: one word for each of my 5 pieces, in order.)

With sustained technical practice, 'looking at sections under a microscope', as my piano teacher described it, and phrase combination through imagery, the program came together in just under a year. During the exam, I found myself sweating profusely, immersed in the joy of music, of simple, pure exploration. It came as no surprise that not only did I pass, smashing the barrier of ATCL, but I scored 90/100, receiving a high Distinction. A year of investigation and study is fittingly characterized by its triumphant final result, a cry of vindication. It can also be remembered through reliving the full journey, from piece selection and analysis to narrative envisioning to all-out strategic practice, to recount the inherent beauty of music and feel alive once more. For we have now secured a foothold in the unspoiled landscape of music as it is and should be, and we would keep our studies going for the next year.

Footnotes

1 Along with ABRSM, these are the two most popular piano exam boards in America. Interestingly, both are British.

2 Love of music and enjoyment of piano is the end goal and the pursuit. The Exhibition Award is merely a chip that fell during that pursuit.

3 who filled my life with beauty and is one of the greatest teachers I've had in any field

4 I intentionally use 'condition' to connote probability, e.g. 'he's too young, he won't pass' or 'others have tried it, and the chance of success is 0%'.

5 The concept of means and ends was eventually formalized in 2019, and I began looking for means versus ends throughout my life since then, but I'm happy to say that I found it first in music, three years prior.

6 or "Rondo a Capriccio in G Major, Op. 129".

7 which is actually an LTCL piece; LTCL is the level above ATCL and equates to a final-year undergraduate level.

8 That's punny.